What is this wine?

It’s classy without that fat, mushy sweetness I dislike so much. In my glass I hold a lovely wine made at great expense and in such lilliputian quantities – as few as just 400 bottles – that hardly a drop will ever seep across the borders of the country where it comes from.

One of the abiding principles of great wine is that it’s made at the frontier, at the margin.

That means where it’s only just warm enough to ripen the grapes. Where that line is drawn varies from grape variety to grape variety, and by such geographical variables as whether a particular vineyard plot faces north or south, and whether it’s a sun trap or a frost pocket.

All this helps to explain that here, in the vineyard of Hoenshof in the Flemish village of Borgloon located west of the border with Germany, just north of French-speaking Belgium and at a stone’s throw away from the Netherlands, a grape called Würzer fares very well.

Würzer is a bizarre and uncommon grape variety. It’s a cross between its parents Gewürztraminer (not Savagnin Rose as the reference book ‘Wine Grapes’ mentions) and Müller-Thurgau. It was created at the German viticultural station, Alzey, in 1932. The variety was only planted in any significant quantity in the 1980s. In Germany 66 ha remain from 121 hectares in 1995. Just 6 ha are grown in England and a few blocks are found in Switzerland and in Nelson in New Zealand.

Another reason is that, as its winemaker Ghislain Houben (alias known as the Professor) explains, this far north the 2013 harvest was particularly good. And, good years do matter in Belgium because the whole country suffers from high annual rainfall and poor amounts of sunshine in summer. The 2013 vintage was qualitatively good but with low yields. And, low yields do matter when dealing with cropper Würzer which tends to give overwhelmingly heady wines with noticeable alcohol levels when grown in warmer climes.

You see, it could just be that early ripener Würzer has found its homestead here, in Belgium, where it can retain its acidity. I believe so. Surely, Hoenshof’s example I tasted during the ‘Wijnfeesten’ in Borgloon last week was the one wine that stood out. It’s a pity, though, that the other Belgian wines presented at this fair are so far simple, everyday wines to gulp down but not to be pondered over. Which of course is not to say that there are no other enjoyable or interesting wines being made in this part of the world. Clos d’Opleeuw for one can be as good as fine white Burgundy.

At this occasion, however,I was more than happy to content myself with the Würzer. The medium-sweet wine gets its sweetness naturally (about 30 to 50 grammes, I guess) from prematurely halting the fermentation process by lowering the temperature of the ferment. In fact, I preferred it to the sweeter white wine Houben makes from air-dried Muscat rose à petits grains, Muscat bleu, Chardonnay and Pinot Gris with its slightly earthy and savoury edge.

Würzer is the wine!

Tasting Note (21.9.2014 G.M.)

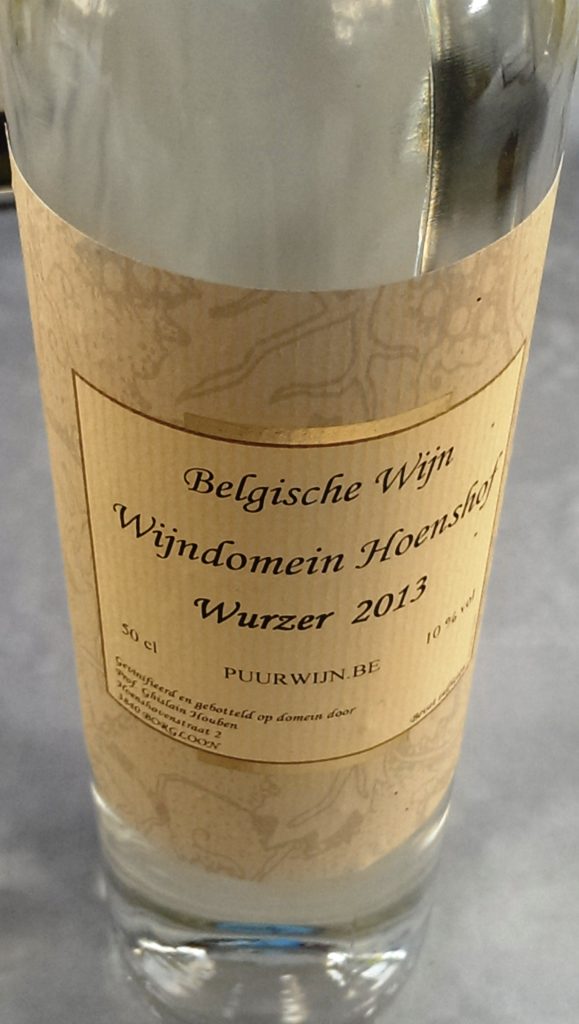

Wijndomein Hoenshof, Wurzer, Belgische wijn, 2013, 10% Vol.

variety: Würzer

style: medium-sweet white wine

region: Belgische Wijn (Borgloon, Haspengouw, Belgium).

producer: Wijndomein Hoenshof

Georges’ Score: B-1Ġeez (but could have been a ‘good’ E for unbelievable eccentric).

This straw coloured white wine has a pale lemon sheen which introduces a fresh yet soft wine. It’s well-made without any piercing acidity or cloying sweetness. It’s delicately perfumed with scents of jasmine, sweet talcum powder and tree bark. The palate is broad, slightly grapey, not reminiscent of any exotic fruits but with sappy pear juiciness and a pinch of camomile. It’s zesty, too, just a little too terse in the end perhaps but the finish is racy enough to make you want more. It’s a generous wine with all Würzer flavours that can go galloping wild kept well reigned in.

Beste Georges,

Bedankt voor de mooie bemerkingen.

Vandaag (26 September) Wurzer 2014 geoogst.

Met vriendelijke groeten,

Ghislain Houben

I have been wondering what happens to the yeast when the temperature is lowered to about -3 degrees Celsius so as to halt the fermentation.

Won’t the yeast just go dormant and reactivate the fermentation again when the temperature rises again?

Dear Arthur,

Yes that is what very well could happen; and the sweetness would be turned into alcohol rendering a dry wine.

However, the process doesn’t stop with “deep-chilling”.

The sweet wine is likely to be centrifuged or filtered to remove the cold-inactivated yeast cells without further loss of sugar.

Once the yeast have been removed the fermentation process is done.

I hope that helps.

Wishing you many more wine discoveries, dry and not so dry!